Update 2020: NgRx has several new releases. Not everything written here is still up to date. I’ll try to update the article as I have time.

NgRx is one of the good options that developers choose to use in their Angular applications whenever the application grows a bit and something is needed to manage the state.

While working with NgRx I’ve found out a series of tips that I would have loved to know beforehand. Some of them I’ve discovered looking at different ways people were handling things and some I’ve found while constantly refactoring the code to make it cleaner and easier to understand.

This series of tips is split into four categories, according to each part of NgRx that they apply to:

Actions

Use classes for all actions

This will grant you awesome benefits like type safety in all the places where you use the action: components, reducers, effects, etc.

This might feel a bit weird when you start using it, as one would prefer the less clutter way of factory methods, but using classes will pay off on the long run:

import { Action } from '[@ngrx/store](http://twitter.com/ngrx/store)';

export const LOG_ERROR = '[Logger] Log Error';

export class LogError implements Action {

readonly type = LOG_ERROR;

constructor(readonly payload: { message: string }) { }

}Once we have this in place we can benefit in the reducer:

export function reducer(

state = INITIAL_STATE,

action: LogError | LogWarning,

){

switch (action.type) {

case LOG_ERROR:

return {

error: action.payload,

};

default:

return state;

}

}In this case we are telling the reducer what kind of actions we expect and we use those in the switch statement below (read on to see how to group them together).

One important thing there is that for TypeScript to be able to infer the type and allow us to benefit from this type of guards we must use readonly on the type property in the class. Normally it’s a property of type string, that can be changed as needed, but adding readonly will make it a string literal, restricting the type to our specific string value and enabling the type guards.

If you export the type declarations, beside readonly you also have to write the properties with an extra typeof:

readonly type: typeof LOG_ERROR = LOG_ERROR;Otherwise the type will be widen to string and that’s not what you want.

We can also have the type guard in NgRx Effects, where it really helps:

@Effect()

logError$: Observable<Action> = this.actions$.pipe(

ofType<LogError>(LOG_ERROR),

tap(action => console.log(action.payload))

)We used ofType to specify the action that this effect will handle and from that point on we can be sure that the payload object is what we expect, meaning an object with the string property named message. This is really useful when you write or refactor the code because the compiler will show an error each time you make a mistake.

Always name the property of the action payload

The Action interface from NgRx states that our class needs to have only a property type of type string. For consistency and some extra benefits, whenever a payload is needed in the action, we should name the property simply payload.

Also, I always prefer to have the payload an object that has other properties even if just one. So for example, in the LogError case one can easily defined it like:

constructor(readonly payload:string ) { }I find it more understandable to have an object and state what that value represents:

constructor(readonly payload: { message: string }) { }Inside a larger app one will have for sure actions that have objects as a payload. Using it like that all the time makes it consistent and easier to read and understand the intent.

Keep all related actions in the same file

Given our logger actions example we can assume we have multiple actions. Even though generally it’s good to have a class per file, in the case of NgRx Actions I find it better to have all the related actions in the same file.

| import { Action } from '@ngrx/store'; | |

| export const LOG_ERROR = '[Logger] Log Error'; | |

| export const LOG_WARNING = '[Logger] Log Warning'; | |

| export const LOG_INFO = '[Logger] Log Info'; | |

| export class LogError implements Action { | |

| readonly type = LOG_ERROR; | |

| constructor(readonly payload: { message: string }) { } | |

| } | |

| export class LogWarning implements Action { | |

| readonly type = LOG_WARNING; | |

| constructor(readonly payload: { message: string }) { } | |

| } | |

| export class LogInfo implements Action { | |

| readonly type = LOG_INFO; | |

| constructor(readonly payload: { message: string }) { } | |

| } |

Group actions in a union type

Following the previous tip, we can group all the classes in a TypeScript union type:

export type LoggerActions = LogError | LogWarning | LogInfo;This will be helpful when we work with them and we want to state that some specific type can be any of the Logger actions without having to write all of them each time.

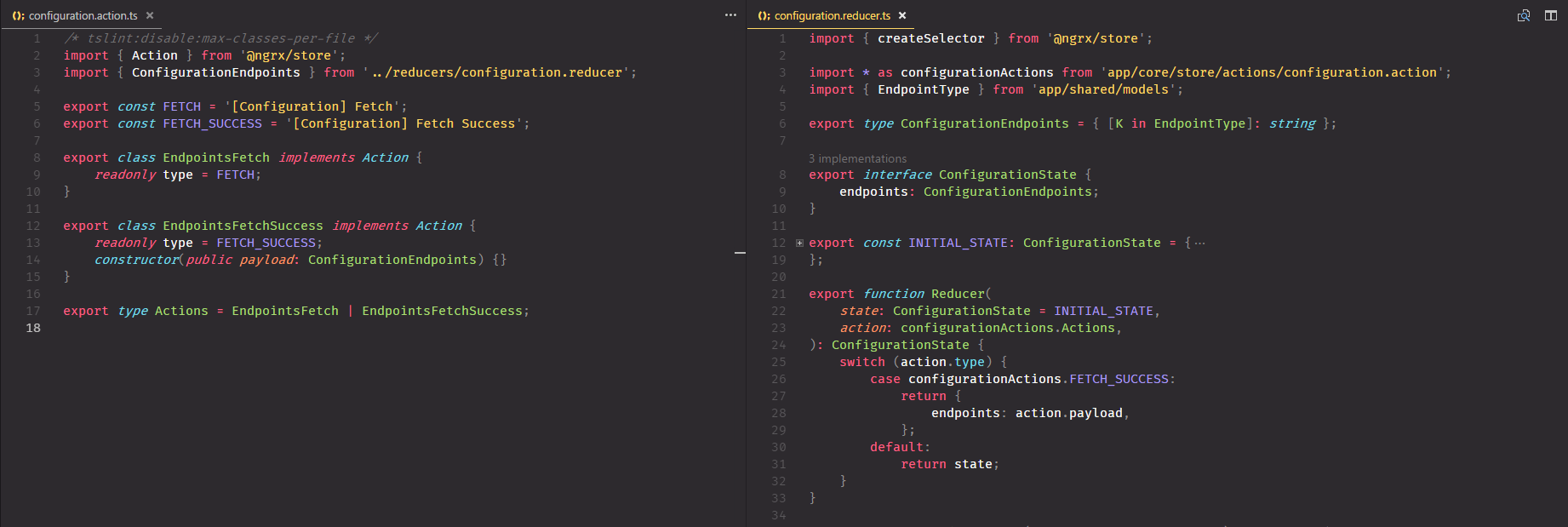

Use short names for constants and classes

In order to show better the intent we usually go for descriptive names. But in some cases this can get out of hand quickly and it could mess up the discoverability when we use code completion to find something.

Suppose we have a Documents entity. We could create actions like DocumentsFetch, DocumentsFetchSuccess, DocumentsSortChanged with the corresponding constants named in the same way. However this will make most of our names quite long and when we want to use an action from here, everything will start with Documents which is not that great.

Since all of the actions are in separate files we can simply use shorter names for them. For constants:

export const FETCH = '[Documents] Fetch';

export const FETCH_SUCCESS = '[Documents] Fetch Success';

export const SORT_CHANGED = '[Documents] Sort Changed';We have ‘[Documents]’ in front for all of the strings though. This string is actually the type of the action and we really want to have them different.

Then we can name our actions in the same way: Fetch, FetchSuccess and SortChanged. Since they are all in the same file we can import everything at once:

import * as documentActions from './document.actions';In this way we sort of namespaced our actions and we always know which action from what type are we using.

Effects

Implement toPayload method

This was actually a part of NgRx but was removed in newer versions. Since most of our actions have a payload property and usually in the transformations that are needed we care only about this, we can create a helper method that will map the action object to the payload:

const toPayload = <T>(action: { payload: T }) => action.payload;Then we can use it in our effects:

@Effect()

public errors$: Observable<Action> = this.actions$

.pipe(

ofType(LOG_ERROR),

map(toPayload),

...

)After the map we can use the payload data without having to refer to it as action.payload.foo each time we want something from there.

As a cleaner alternative we can use destructuring to fetch the payload property:

@Effect()

public errors$: Observable<Action> = this.actions$

.pipe(

ofType(LOG_ERROR),

tap(({ payload }) => console.log(payload)),

...

)Not all effects have to emit something

Usually we create an effect to catch a specific action, do some processing and then emit one or more different actions. But we don’t have to do this all the time.

We can specify that we don’t want to do this and just do some side effect whenever a certain action takes place:

@Effect({ dispatch: false })

userLogout$ = this.actions$.pipe(

ofType<userActions.Logout>(userActions.LOGOUT),

tap(action => console.log('User is logging out', action))

)As you can see above this is handled by setting the dispatch property to false.

Load data with effects

The purpose of an NgRx effect is to handle any side effects that we have in our application and one of this type of side effect is making AJAX calls to load data from an API. This is done by most developers using this library but I’m adding it here for completion.

So instead of loading data directly we do this with an effect. Assuming the user has a button that can be pressed to load some documents, when this happens we simply trigger an action to notify that we want to do this: documentActions.Fetch.

Inside an effect we catch this action, make the request and map the outcome to a success action:

loadDocuments$ = this.actions$.pipe(

ofType<documentActions.Fetch>(documentActions.FETCH)

switchMap(() =>

this.documentsService

.getDocuments().pipe(

map(docs => new documentActions.FetchSuccess(docs))

)

)

)And then we have a reducer that listens for this FetchSuccess action and puts the new documents in the state.

In this way all the requests are isolated from our application and we have a central place to do each of them. We might have multiple places from which we can trigger a documents fetch and all we have to do is send the fetch action.

Always handle errors

The actions stream is an Observable, this means that once an error occurs it’s done, that’s it, no more events will occur and we really don’t want this since it will block our application.

So we always need to make sure we handle things. This means making requests on a different stream that we then merge with operators like switchMap and always handle errors there.

So a more complete example of fetching the documents would be:

loadDocuments$ = this.actions$.pipe(

ofType<documentActions.Fetch>(documentActions.FETCH)

switchMap(() =>

this.documentsService

.getDocuments().pipe(

map(docs => new documentActions.FetchSuccess(docs)),

catchError(err => of(new documentActions.FetchFailed()))

)

)

)The actions stream is the main one that all our actions are emitted onto, so when we want to make a request to load the document, that might fail, we do it inside a switchMap operator where we catch the error and return a different action.

Effects are services

This is an easy thing to forget, but Effect are services in Angular world and we might use Dependency Injection to get instances of other services in them.

For this to work we need to add the Injectable decorator to the class.

Reducers

Keep them simple

Here I have only one tip, keep reducers as simple as possible. They should be clean and don’t have any logic inside. A reducer should only take the data from the action and update the corresponding part in the state with it, it should not make any decisions or any kind of logic that will be hidden there.

The official sample app exemplifies this in a good way, this is how a reducer should look:

| export function reducer(state = initialState, action: AuthActionsUnion): State { | |

| switch (action.type) { | |

| case AuthActionTypes.LoginSuccess: { | |

| return { | |

| ...state, | |

| loggedIn: true, | |

| user: action.payload.user, | |

| }; | |

| } | |

| case AuthActionTypes.Logout: { | |

| return initialState; | |

| } | |

| default: { | |

| return state; | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } |

If you have something that looks more complicated than this there is place to refactor and make it slightly better.

General

Use selectors

On the store class we have the select method, and there also is a pipeable select function. We can use both of them to fetch a part from the state in places where it’s needed.

While you can pass the keys/path to what you want to fetch as a string argument to these functions I recommend using the createSelector function provided by NgRx which, as the name suggests, allows us to create a callback function that knows how to fetch a part of the state.

For example something like:

export const getLoggerErrors =

createSelector(getLoggerState, (state) => state.errors);Where getLoggerState is a generic way to get the part of the state responsible for the router:

export const getLoggerState = (state: AppState) => state.logger;And then whenever we want to select something we use these kind of functions as an argument to select.

This has several benefits:

-

we can change the way our state looks behind the scenes without actually changing the app code, since the selector will be the same one

-

we can group together different parts of the state and get what we need

-

the selectors use a technique called memoization which basically means that once we call one with some arguments it will store that result and whenever we call it again it will return the cached result without executing the function

There is a lot of good info about selectors in the official docs.

Normalize data

We should think of the state like a local, in memory database. One important thing we should not do is duplicate the same information all over the place.

So for example if we have a list of items we can keep it in one place and if we need a list of selected items we just hold a list of ids, those that are selected. Whenever we need them we create a selector that gets the list of items and the selected ids and map them together to get the result.

This is important because we don’t want to update multiple parts in the state when one single action occurs.

Also there should not be that many nested levels of data, as this will get tricky to manage and select when needed. A common approach here is that instead of keeping items in arrays, we keep them in objects and use the id as an identifier. This needs a bit of time to get used to but it pays of in the long run.

If normalizing the state in this way gets too complicated to do by hand there is an awesome library called normalizr that can help a lot with this.

{

result: "123",

entities: {

"articles": {

"123": {

id: "123",

author: "1",

title: "My awesome blog post",

comments: [ "324" ]

}

},

"users": {

"1": { "id": "1", "name": "Paul" },

"2": { "id": "2", "name": "Nicole" }

},

"comments": {

"324": { id: "324", "commenter": "2" }

}

}

}This is how a normalized state would look if we have a blog post containing articles, users and comments. Have a look at the normalizr documentation for more info.

Another benefit of keeping the state like this is that it will allow us, more easily, to add a caching layer to our application. Only loading data when we don’t have it, or what we have is outdated.

Don’t use the store all over the place

This is more about ‘dumb components’ than anything else. Most of our UI components should be small and dumb, meaning they should not know that there is a state, how we fetch data and so on.

Generally we have containers, meaning a parent component that fetches from the state all the required data and triggers all the required actions and all the small components inside only have a few Inputs and Outputs to handle what they need to display.

Generic error action

When we load data using NgRx Effects we’ll end up having lots of actions that trigger the load, those that mark the load success and those that show when an error occured.

We can make some of them generic, for example the error ones. In my experience we tend to use the other ones in more places and need them explicitly, but if this is not the case you can make those generic as well.

For example this is how a generic error action would look:

| export class ErrorOccurred implements Action { | |

| readonly type = ERROR_OCCURRED; | |

| constructor( | |

| readonly payload: { | |

| action?: Action; | |

| error?: ErrorData; | |

| }, | |

| ) {} | |

| } |

It has a payload with an action property, this will specify which action triggered the error. For example if an error occurs while we were doing a FETCH_USERS action, this will be used here. We have it as an action with the type property inside for consistency and ease of usage, we could have just as easily have this as string and store the action type only.

The error property is of type ErrorData and will hold more information about what went wrong. You can model this as need, for example I generally use something like:

interface ErrorData {

type?: string;

error?: any;

}Then when we can use this in Effects where we handle the error case:

| loadDocuments$ = this.actions$.pipe( | |

| ofType<documentActions.Fetch>(documentActions.FETCH) | |

| switchMap((action) => | |

| this.documentsService | |

| .getDocuments().pipe( | |

| map(docs => new documentActions.FetchSuccess(docs)), | |

| catchError(error => of( | |

| new ErrorOccurred({ | |

| action, | |

| error, | |

| }) | |

| )) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| ) |

Property initialization

Initialize directly all selector properties when defining them instead of constructor or other places. One can have code like:

| export class DocumentContainer { | |

| companyName$: Observable<string>; | |

| documentStatus$: Observable<number>; | |

| constructor( | |

| private store: Store<AppStore.AppState>, | |

| ) { | |

| this.companyName$ = this.store.select(detailsSelector.getDocumentCompanyName); | |

| this.documentStatus$ = this.store.select(detailsSelector.getDocumentStatus); | |

| } | |

| } |

Where we first define the properties and then we initialize them in the constructor. Ideally we can do it in one place while having less code that is also easier to read. This would have the same effect:

| export class DocumentContainer { | |

| companyName$ = this.store.select(detailsSelector.getDocumentCompanyName); | |

| documentStatus$ = this.store.select(detailsSelector.getDocumentStatus); | |

| constructor(private store: Store<AppStore.AppState>) { } | |

| } |

Hopefully you’ve found some good tips about using NgRx above 😃.